Innovation on menstruation and sex education on the Mekong

Sovanvotey Hok, aka Green Lady Cambodia, is an advocate for women’s health in a country where cultural barriers can often slow progress. She attended the #ICPD25 summit in Nairobi in 2019, where she was inspired to start her innovation initiative to deliver youth-created sex education to schools across the country.

Votey is working with high school students to accelerate the implementation of sex education. “We want to do it ourselves by asking the experts,” Votey says. “By asking people who used to work on sexual and reproductive health, we have some of the content we need, and now we’re trying to get comprehensive sex education papers translated so that they are more accessible.”

Votey considers it essential that young people produce the learning materials so that they connect with other students across the country. “The high school students will do it themselves,” she says. “All volunteers will be from 10th grade and 11th grade.”

“The high school students will do it themselves. All volunteers will be from 10th grade and 11th grade.”

Votey and her team are planning the sessions and how they will allow students to choose the areas that interest them: “They will be divided into two teams and one team will be called the innovations or technology team. And then the other team will be called the content development team.” The technology team will learn coding using Raspberry Pi keyboard units and will work with the content development team to bring the modules together. The goal is to support the students to create a series of video game-style lessons with characters, questions and games.

Votey says that comprehensive sex education for Cambodian girls is urgently needed: “Sadly, we lag behind even conservative countries like Indonesia in talking about sexual and reproductive health in the education curriculum.”

For Votey, it has been a long journey advocating for change and now COVID-19 has delayed it even further. “The Cambodian Government promised in 2018 that sex education would be included in the education curriculum in 2020,” she says. “Then we understand that because of COVID-19 it has to be delayed, and now it’s pushed out to 2022.”

Votey reports that it has been a challenge even getting agreement on terminology. References to “sexual and reproductive health” had to be changed to “sexual health and reproductive health” to assuage sensitivities in the Government. “It doesn’t sound ‘appropriate’, they say. It doesn’t sound ‘cultural’. So even the name itself has a lot of problems.”

Votey says that local experts, educators and United Nations agencies have been developing materials for years: “The curriculum already has everything, but then it gets rejected by the Government. The people who have the power say that it’s too culturally sensitive and that, if we talk about sexual and reproductive health, it’s the tip of the iceberg.”

“The people who have the power say that it’s too culturally sensitive and that, if we talk about sexual and reproductive health, it’s the tip of the iceberg.”

Votey thinks the resistance to having classroom discussions about sexual and reproductive health is an attempt to avoid discussions on more troubling realities. “It’s not just abortions that we need to talk about,” she says. “Gender-based violence, harassment in the workplace and rape all get ignored when you don’t teach children about their bodies in schools.”

Votey has seen the uphill struggle that women face in reporting rape in Cambodia. “In cases of rape, women have to be brave enough to seek help or support at the hospital or the clinic,” she says. “Some girls say it’s too shameful and they are so embarrassed because the provider asks them a lot of sensitive or uncomfortable questions.”

“Some girls say it’s too shameful and they are so embarrassed because the provider asks them a lot of sensitive or uncomfortable questions.”

The scale of the problem and the need for women’s groups to network and develop community-based systems are clear, but Votey has found that government representation at workshops on women’s health has stifled open discussion. “If we have a meeting with just 10 people to talk about sexual and reproductive health, there has to be two government representatives to observe and investigate,” she says. “The Government requires this because they say that it’s a sensitive cultural issue.”

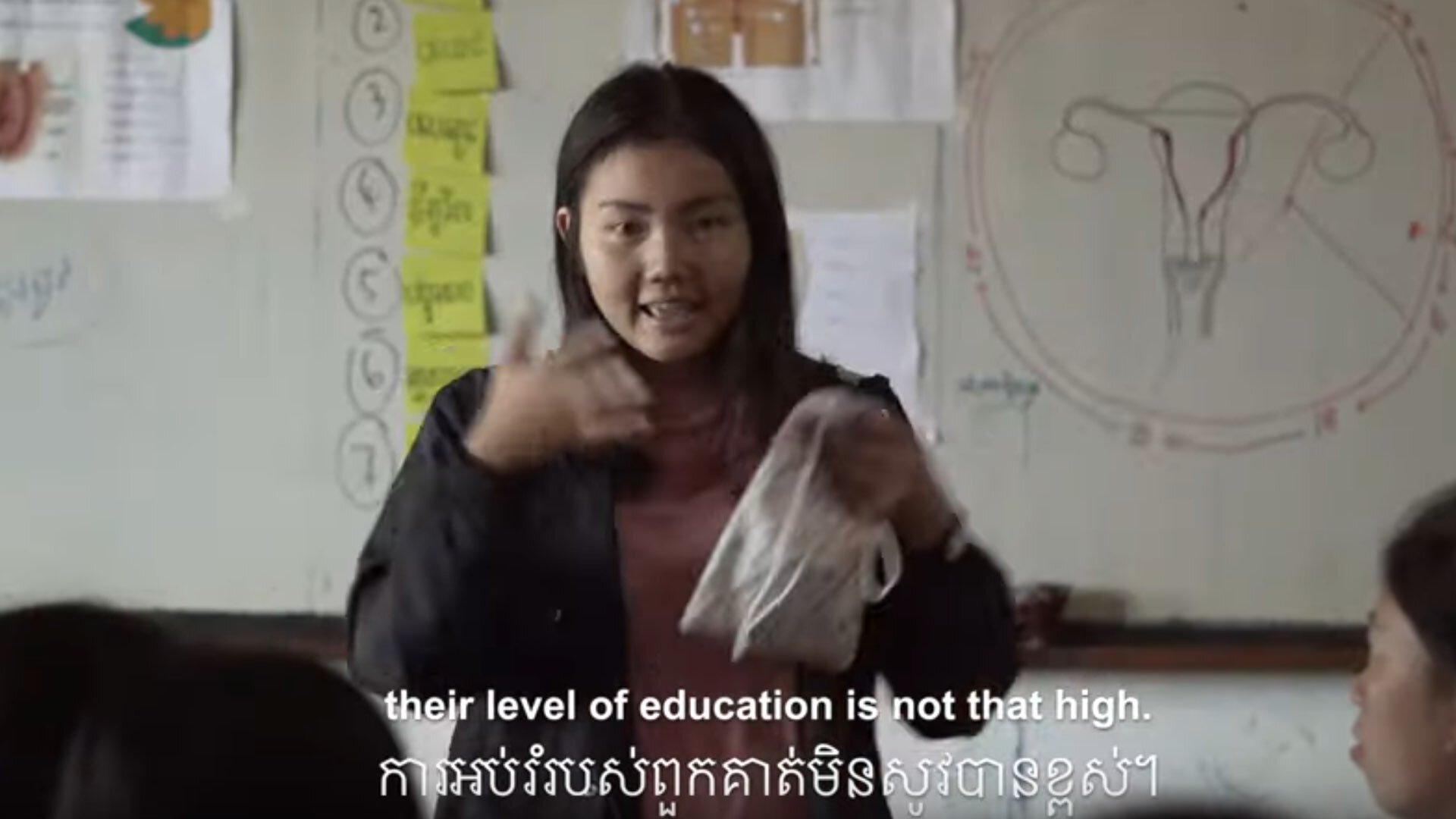

Votey has looked for ways to engage young people directly so that these sensitive subjects can be talked about in a positive way. She started Green Lady Cambodia as a way of opening discussions about menstruation. “I want to introduce washable pads to Cambodian girls and women,” Votey says. “Get the washable pads out there and stop women from thinking that they have only one choice.”

Opening a discussion about pads breaks the ice and girls are able to talk about other issues they face. “Girls worry about blood – menstrual blood, period shaming and body shaming,” she says. “But we understand that talking about this is part of progress towards sexual and reproductive health.”

Votey saw the fluctuations in donor funding cycles as a challenge to building a sustainable operation, so she created Green Lady Cambodia as a socially conscious community enterprise. “We need to sustain, we cannot just wait for the funding all the time,” she says.

“Girls worry about blood – menstrual blood, period shaming and body shaming.”

Votey reports that she is getting more support from leaders eager to see civil society advocating for change: “The Minister of Women’s Affairs, when she met with us, she encouraged us not to hide ourselves and to be in the light so that people can see and observe.

Votey has recognized the opposition to sex education and has developed workaround solutions so that the process can move forward. She says that using innovation and technological tools such as video helps the Government to support the project: “If you talk about the Ministry, they will be happy to see the students doing the project and having fun education rather than us.”

Helping teachers who have had limited exposure to sex education is another benefit of the project. “The teachers are shy about it,” Votey says. “They are not equipped with enough training or enough confidence to do these things. So it will be a happy thing for them to be able to learn with the students.”

“The teachers are shy about it,” Votey says. “They are not equipped with enough training or enough confidence to do these things. So it will be a happy thing for them to be able to learn with the students.”

Votey attended the #ICPD25 summit in Nairobi in November 2019 and got a chance to connect with activists from around the world. “There were a lot of socially difficult topics and conversations,” she says about her time in Nairobi. She was deeply moved by members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LGBTQI) community sharing their stories so openly and she realized she could be an ally in her country in the movement for rights and dignity. “I remember seeing all the straight people who supported the LGBTQI community and I thought, ‘I would love to be one of the people who support the community.’ The idea is so new in Cambodia.”

Votey was inspired by the courage of other advocates but also by the ideas and the technology presented at the summit to help deliver these rights and services. She says that one of the things she loved about the Nairobi summit was the Pajoma Zone. “It’s a youth-friendly space, where I got to talk about my own topic of menstruation,” she recalls. “There were a lot of topics, a lot of mind-blowing technology and data-collection research.

Nairobi expanded Votey’s notion of what is possible. “I’m still using Excel,” she says. “But others have cool tools like maps with pins that help you know where people are and what they need. It’s amazing and I would love to know more about these things happening in the world.”