Reaching rural Mongolia with comprehensive sexual education

Mrs. Nergui teaches Biology and Health Education in Umnugobi province, Mongolia. She’s been teaching the subject for 18 years at School №1, Dalanzadgad. She also presents the tele-health sessions produced by UNFPA.

Nergui says sexual health and education in Mongolia is taught by biology teachers, which results in different levels of emphasis and various degrees of comprehensiveness.

“I was assigned to teach the subject just like other Biology teachers,” she says. “All Biology teachers were expected to teach Health education no matter their level of interest. I am personally really interested in health education, so I am confident to teach the subject.”

She says this varied approach to sexuality education has resulted in gaps in important knowledge about sexual health.

“Students come into the class with different knowledge levels on certain topics,” Nergui says. “Some know well about reproductive health while others have no idea about it.”

“Students come into the class with different knowledge levels on certain topics. Some know about reproductive health while others have no idea about it.”

She says the conversation about our bodies has to start early in school with basics about hygiene.

“I would expect students to be educated on personal hygiene in kindergarten or at least in primary classes,” she says. “But in reality, some students are way behind.”

Nergui says the uneven access to reliable information about sexual health comes from weakness in the education materials.

“This knowledge difference has a lot to do with the gap we had in the Health Education curriculum,” she says. “When students are not on the same page, it requires me to return back to health subjects that are not in the actual content and start teaching over on certain topics.”

Nergui says there are real consequences for Mongolian women and girls when there are gaps in health education, like with COVID-19.

“Most of the girls get information about sexual and reproductive health from the in school classes,” Nergui says. “So when the subject was interrupted, this information went missing. It became inaccessible for many girls, especially in rural areas.”

“When the subject was interrupted, this information went missing. It became inaccessible for many girls, especially in rural areas.”

She says this breakdown in sexual health education leaves the girls more vulnerable.

“They step into adulthood without appropriate and informed understanding,” she says. “It is scary to enter the world that you have little or no knowledge about.”

Nergui says the impact on the girls can be long-lasting.

“Many girls risk engaging in undesirable relationships. There is a rise in adolescent birth rates and unwanted pregnancies.”

“Many girls risk engaging in undesirable relationships,” she says. “There is a rise in adolescent birth rates and unwanted pregnancies.”

Nergui says there are cultural sensitivities around sexual education in Mongolia.

“Traditional concept of gender norms is still quite strong among older Mongolians,” she says. “Some of our health subjects are criticized and debated.”

She says it’s rare, but occasionally she’s challenged by parents for what she teaches.

“I sometimes have parents approaching me and judging me for teaching sexual education to their kids,” she says. “They think that I am promoting sex life. There were times when parents blamed me for their children’s misbehavior or choices in life.”

Nergui says there’s a direct correlation between opposition and education.

“I observed that those who are most judgmental are those who have less knowledge about SRH education in their background,” she says. “ I am glad that the concept is shifting gradually among younger generations.”

Nergui worked with UNFPA to produce a series of their tele-health lessons to help reach young people.

“With COVID-19, schools were closed for 2/3 of the time,” she says. “Tele-lessons replaced teachers. When students returned to school this September I could tell who followed Telehealth sessions and who did not.”

She says the lessons help create an even and comprehensive handling of the subjects.

“The tele-health session was very effective for students who didn’t lose their engagement throughout the period,” she says. “When we returned from quarantine, it was easier to teach those students following the curriculum.”

Nergui says she can’t move ahead with new lessons until all her students are caught up.

“Personally I couldn’t move on ignoring those who didn’t follow the tele health session, she says. “I had to recover sessions that are supposedly taught in previous years just to have the students on the same page on certain topics.”

“I encourage interactive approaches with group discussions.”

She says making the lessons engaging and relevant for young people is a constant challenge.

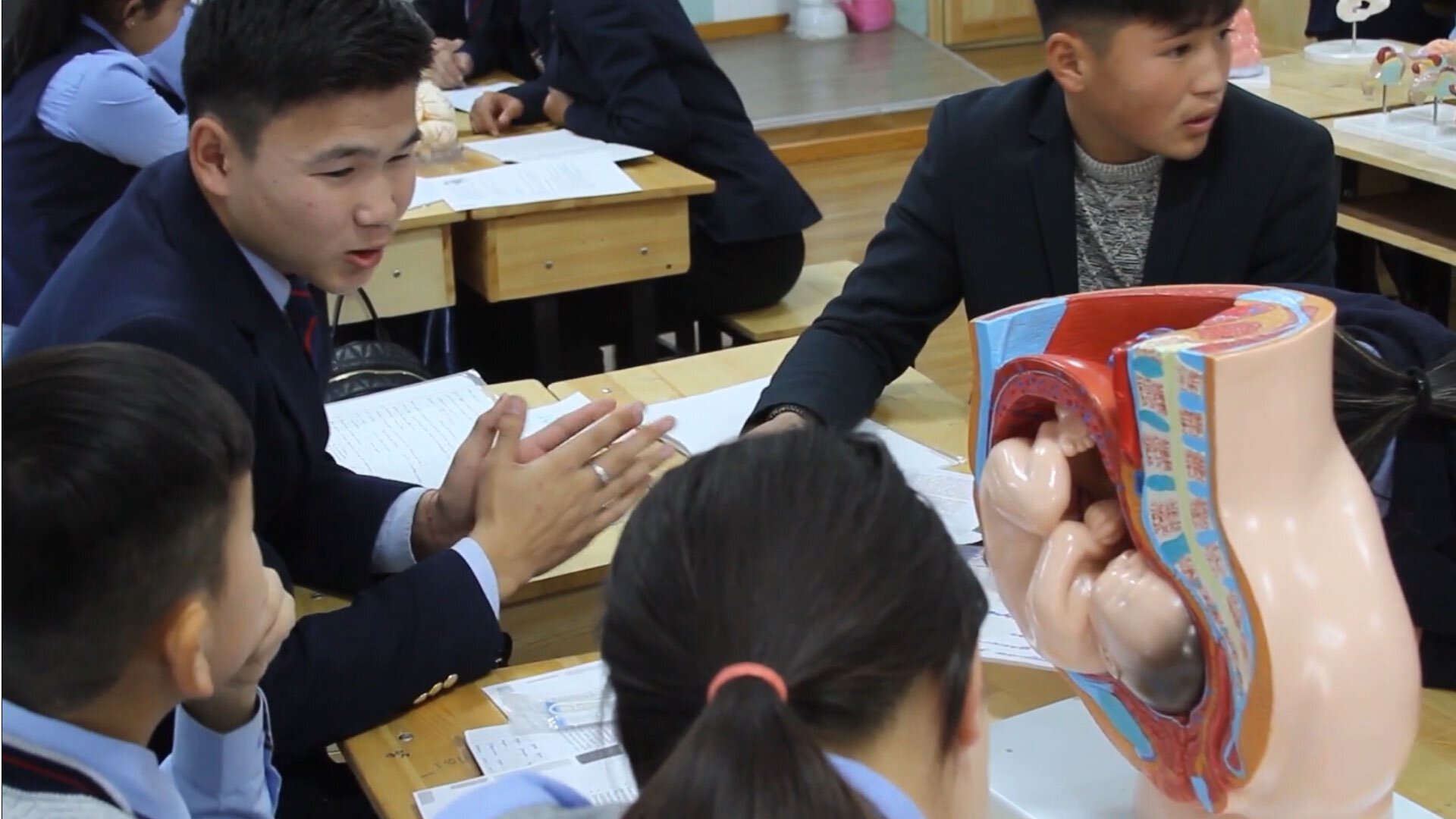

“I like to have our students work on case studies, have them identify problems, solutions and prevention measures,” she says. “I encourage interactive approaches with group discussions.”

Nergui’s school has a Health Education cabinet funded by UNFPA Mongolia through their Integrated Support Programme in the province. The Cabinet is m equipped with moulages and displays for teachers.

“Health moulages are not cheap and not easy to find like other materials,” she says. “Having resources like this really stimulates students’ interest and engagement in the study.Thus kind initiative is essential for the impact of health education.

Nergui says she hopes the project will have a long term positive impact.

“The content is close to our daily lives, it is familiar and useful,” she says. “During lockdown, if a student is watching the tele-session other family members are also hearing and seeing what it is taught. Then some families discuss topics among themselves to get collective understanding on health issues.”

Nergui says the key to accessing good information is asking questions.

“I advise my students to be as open as they can, not to be afraid of approaching me or other reliable people if they have any concerns.”

“I advise my students to be as open as they can, not to be afraid of approaching me or other reliable people if they have any concerns.”

She says most of the time it’s about being the right trusted person and then connecting them with other support.

“We are not experts,” she says. “I refer my students to the Adolescent Cabinet doctors where they can get more professional support and information.”

Despite the gaps in sexual and reproductive health in Mongolia, Nergui says there are signs of real progress.

“I think people are more open and confident to talk about sexual and reproductive health compared to the old days,” she says.