‘The kits are life-saving’

Febby Gibson worked with the Family Planning Organization of the Philippines and in partnership with the NFP Philippines. She started as a youth volunteer then she went into the Humanitarian Department as an SRH trainer partnering with government officials in the health department.

Febby has been through dozens of natural disasters and humanitarian responses. As a recently graduated nurse, she volunteered to help women and girls in the strings of disasters that hit the Philippines from 2010-2018. After four years she was appointed to a leadership role where she was responsible for coordinating with government officials.

“It's terrifying,” Febby says. “You need to communicate with public officials and health workers and during that time, they've never heard of it and as a young person coming into this meeting, trying to give them an idea of why we're doing such a response.”

Febby says when she started her career, the majority of leadership roles in government disaster response were done by men and there was little appreciation for why women’s health was such a key priority.

“It could be intimidating because they would look at me and they would say, ‘Who are you?’ Febby recalls. “They've never seen me before I'm new to the place and I came in talking about having a medical mission particularly for pregnant and lactating women. It was a new idea for them because for them they're responding to the whole population.”

“It was intimidating at first, but through time I learned how to communicate well with officials.”

Through regular meetings of the emergency clusters, Febby continued to make the case for special services for vulnerable groups. She says it was challenging but she started a constructive dialogue.

“It was intimidating at first, but through time I learned how to communicate well with them,” she says.

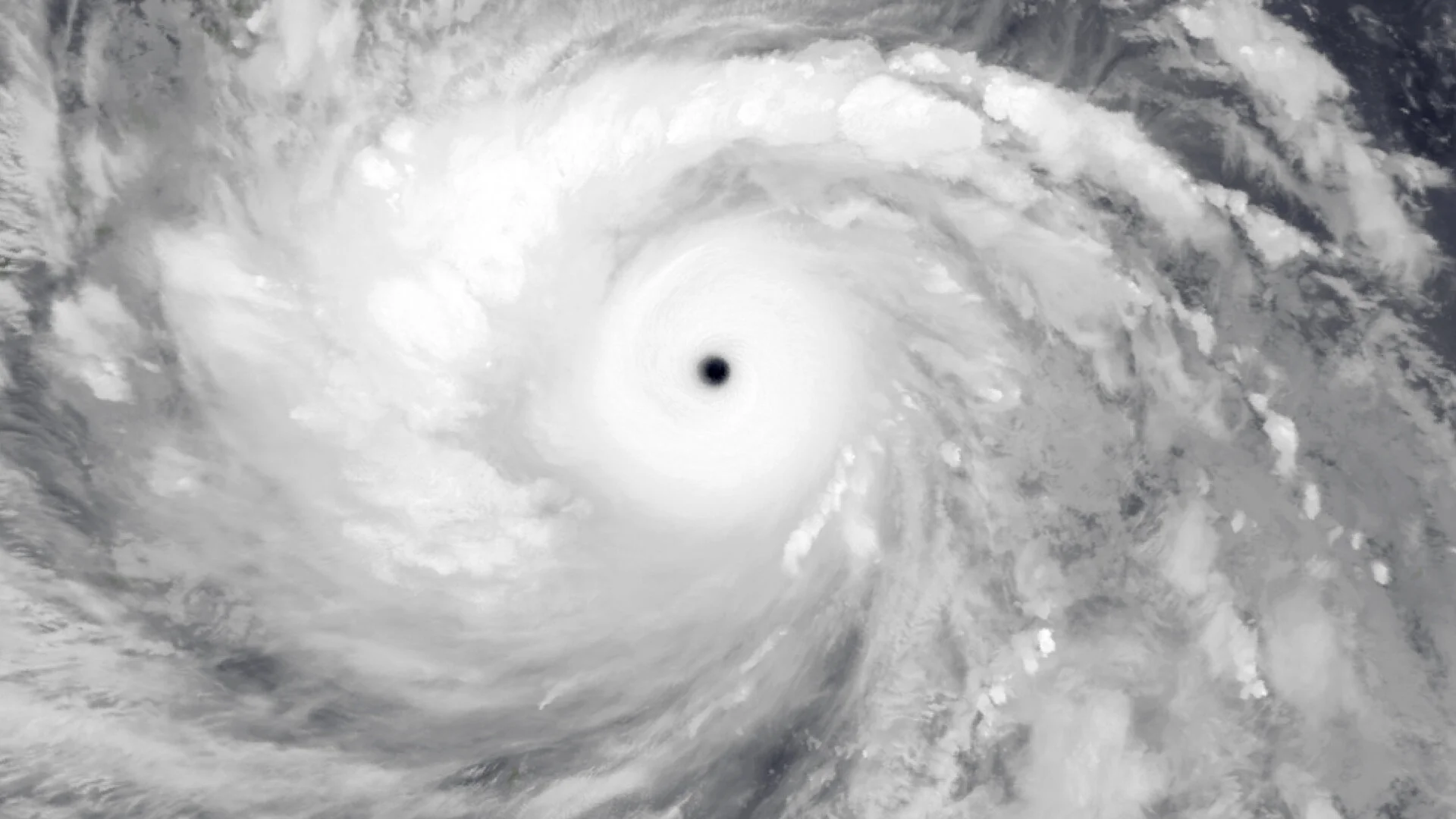

Febby has been through several disaster areas and seen firsthand the devastation of deadly cyclones. She says the scale of destruction is so vast that the needs of women, girls and the most vulnerable are often overlooked.

“The needs of these particular women during disasters are forgotten,” Febby says. “Leaders would try to have this service that they think it will suit for everyone. These decision makers are more about responding to the greatest number of the people instead of really looking into the needs of each vulnerable group.”

Febby says that she sees attitudes shifting and real progress being made.

“The Philippines has moved a long way in making sure there's a preparedness plan that is responsive to women,” Febby says.

She says that building good relationships with government partners at every level is a key ingredient in disaster planning.

“Build a good partnership with the different sectors in the government before a disaster” she advises. “It's good to have this kind of talk outside of a crisis. It's good to be able to educate decision-makers.”

She says the training and education on women’s health differs in each community and with different actors in the response.

“With health workers it’s about training so that these services should be in place in their preparedness response. So these vulnerable groups will not be left out during a disaster.

Febby says that building a good relationship beforehand will make it easier for them to implement the response.

“It’s about having champions or training specific people, like a politician or decision-makers from the Health Department training them into MISP or DRR.”

She says that part of building relationships with the government and partner is taking time to reflect on how to improve after each disaster.

“We take time to reflect or evaluate the lessons learned that we gathered during a certain response and try to bridge the Gap that we had for the certain response.”

“One response to a certain area may be totally different from the other.”

She says there's no one size fits all solutions.

“One response to a certain area may be totally different from the other,” she says. We need to develop flexibility internally in our strategies and how we implement them.”

Febby says the work is rewarding but it can be personally challenging.

“Personally could be draining in a way, Disaster Response is really away from home. So I wasn't able to go home and be with my family in December. Christmas is a big thing in the Philippines, but it’s also typhoon season.”

She encourages all humanitarian works to prioritize their mental health and take time to recover.

“That's one thing that we've learned with our team,” she says. “There should always be a time where humanitarian workers have time to have a break.”

“Being able to influence decision makers with what we are doing and inspire them that this is something that is rewarding.”

Febby says she’s struck by the lasting impact of how changes in attitudes approaches continue to resonate.

“Being able to influence decision makers with what we are doing and inspire them that this is something that is rewarding not only for the women in that area, but also, having more health workers who would later be an advocate for reproductive health is quite rewarding.

Febby says she'll always recall the story of a young mother she met after Typhoon Haiyan.The teenager arrived at the remote clinic with a very ill newborn baby..

“I went to talk to her but she said she was too afraid to go to the hospital,” Febby recalls. “She didn’t have anyone, she didn’t know what to do.”

Febby reacted immediately and called a doctor to help the girl and the baby.

“We got her a doctor, and they sent her immediately to the hospital to have her baby checked,” she recalls. “We talked to her and assured her that we will be with her all throughout the way.”

Febby says that because of the high demand at the hospital and the limited supplies, they were prioritizing patients based on need. She did everything she could to help the pair get help.

“We talked to the hospital and talked to the doctor to make sure that her baby is well taken, well cared for,” she says. “We assured her that she will not be charged anything because that was one of her big concerns.”

Febby says a few months later, a young woman approached her but she didn't recognise her.

“The girl says to me, ‘You know my baby, look he’s well now!’’’

Febby says the girl was holding a big healthy baby and could not recognize her.

“The mother was so young she was not able to realize that she has a right to seek these services and benefit from them.”

“Suddenly I remembered her being the young mother with the sick baby,” she says.

When Febby discussed it with the doctor at the clinic, her colleague confirmed that it was a life and death case.

“I remember the doctor telling me that if she didn't send the baby, or if she went there a day late the baby would have not survived.” Febby says. “Being able to be at the right place at the right time means we're able to actually really save lives. It's tangible evidence that that particular time the life of this baby was saved.”

As Febby reflects on the unforgettable experience, she says it’s an example that proves the point for helping vulnerable groups overcome barriers to services.

“The mother was so young she was not able to realize that she has a right to seek these services and benefit from them,” she says.

Febby kept in touch with the girl and she has gone on to become a community leader in women’s health and helping other young mothers get medical care.

Despite success stories like this, Febby says there are always cases of postpartum deaths in disasters. She recalls how one young woman gave birth at a facility and was sent home.

“They didn't know that she's still bleeding heavily,” Febbay says. It was too late when they sent her to the hospital because she was still bleeding profusely.”

Febby says she’s also seen firsthand the importance of prepositioning supplies for women and girls.

“The kits that we use are life-saving.” she says. “Especially in the initial response when you actually go to a disaster area; there are always pregnant women and women who recently delivered.”

She says the kits help fill a crucial gap and help health workers deliver critical services. She says in Typhoon Haiyan the hospitals are destroyed, there was no facility to cater to women who are about to give birth.

“The kits that we use are life-saving.”

“We have these kits that we are able to provide midwives to at least cater to women in childbirth to support deliveries in a sterile way lessening the possibility of complications during or even after birth.”

Febby says the needs of women are essential in planning because there is no way to stop babies being born.

“You cannot stop a woman from giving birth,” Febby says. “Health systems need to plan for that reality.”