Fenualoa's uncertain future

A culture that has thrived on the reef islands of Temotu for hundreds of generations is trying to survive in the face of climate change

Riding into a choppy storm on a narrow banana boat heading into open sea is an unnerving experience. Santa Cruz is behind me and so too are the buoyant feelings of confidence that were present at the start of the crossing to the reef islands of Temoto. The boat was taking us out over the crack in the tectonic plates that stretches from Alaska to Antartica, over the Ring of Fire thrumming fathoms below. In the distance, as the storm clouds cleared, you could just see the volcano Tinakula that erupted only 3 months before.

The clouds of ash have cleared but on the day of my crossing, heavy grey clouds engulf us on all sides and the boat thrashes me into a misery that is the unique discomfort of sea-sickness. But my uneasiness was made far worse by the complete inability to see where we were going. Only storm clouds and the receding peaks of Santa Cruz, as we head closer to these coral atolls that have been home to Melanesian culture for more than 10,000 years.

As I awoke from my stupor and the clouds cleared, in the distance clusters of trees clung to the water like floating forests. We rounded the point and entered the merciful calm of Fenualoa lagoon and the skipper guided us to the lone stick in the water signalling where the chief lives.

The crescent -moon-shaped island opens to the northwest, offering a long sandy beach that looks out to the distant volcano and the endless Pacific ocean. The southern and eastern sides of the island are sheer cliffs that have protected the community from storms for generations. The whole forested island slopes gently downhill to the beach and the community stretches along a single footpath from one end of the crescent to the other.

I dive into the lagoon fully clothed and wash the memory of the rough crossing away. Soaking wet I then met the chief and his family and settled in.

Chief John Akeso has been leading his people for more than 20 years. When he was appointed chief in 1996 he says they didn’t know what climate change was. It’s now become an existential threat that imperils the future of the entire community.

The role of chief in remote parts of the Solomon Islands and other parts of the Pacific is to be the last word on all things. There are no police or government officials here, just the authority of the chief. He’s the judge, town planner, cultural custodian and all-around decision-maker for all of the 1500 people he represents.

The chief explains that the place where we’re sitting used to be well inland and erosion has chewed through meters of the beach and their properties. This persistent loss of land has forced people further inland on to the premium and limited land for growing crops. The careful balance that has sustained his people for millennia has been thrown off and he now faces the abyss of seeing his culture devoured by the sea or scattered on the wind.

He says that managing land and water resources takes up a lot of his time. As houses get swamped in storms or king-tides, they clear coconut and banana tress to make space for the new homestead, safely away from the angry sea. But each tree cut down reduces a source of food. Perhaps the most important responsibility of the chief is to make sure that everyone has enough to eat in this community where self-sufficiency is not a lifestyle choice, it’s a necessity enforced by the sea.

While other communities in the Solomon Islands are torn apart by chiefs decisions to invite Malaysian logging companies to cut their trees, Chief John in Fenualoa doesn’t face that dilemma. The island has no timber, no mining prospects and above all it has no water.

With no streams, ponds or waterfalls, people have lived for centuries with hand dug wells in each household. The rain watered the tree crops and the groundwater was fresh. But the wells are increasingly salty because of rising sea levels.

A year ago the community was facing a water crisis and the idea of having the abandon the island had become unavoidable. Government support has helped improve wells and added rain water tanks and even a desalination unit, so the crisis has been deferred, and the community can breathe a collective sigh of relief for now. The reality is that sea levels are rising dramatically and the improvements have bought a few years time. It’s now up to the chief to use this reprieve to coordinate a dignified transition to the bigger island.

Climate change looms over everything on the reef islands. People may go about their normal lives of fishing or growing food or looking after children but every aspect of life is impacted by it. I went to meet a woman named Janet who’s been trying to cope with the changes in weather. Like every woman on the island, she does much more than one thing: she fishes, keeps pigs, cooks, cleans, gardens, grows crops and raises kids. She says the salty ground water killing off her fruit trees. Some bananas trees have already died and the much prized betel nut tree has stopped producing. The lack of betel nut is itself a small crisis, as people are addicted to chewing the kernel and everyone accepts the red teeth and copious red spit bombs as an acceptable price to pay to enjoy the national obsession with this nut.

But beyond the salty soil and ground water, the changes in rainfall patterns are also hitting Janet and her family hard. The wells are close to the homes on the beach and the crops are grown up into the bush. But there’s no water for irrigation and parts of the food supply can perish in the extreme heat and prolonged droughts.

Janet kept on noticing new fruit tree seedlings dying in the heat. Replenishing the stock of productive trees is an essential part of planning for feeding the hungry mouths of the future. But again and again, Janet saw these young trees flounder and die. She looked around the modest compound of leaf huts in her household and saw a dugout canoe that had been leaking and was on the to-do list to repair. She went to the forest and brought back bags of rich soil and leaf litter and she filled the traditional canoe.

Janet found that she had the perfect raised bed for growing stronger seedlings and garden crops. The raised beds were safe from the salty soil and the extreme heat. The canoe can be moved if it’s getting too much sun and it brings the food cultivation right to her doorstep so her kids get more fresh greens to supplement the diet of fish and taro.

She’s inviting other members of the community to see how she’s growing in the canoes. She says others have been inspired by her lead and are trying the canoe gardens at their houses. It’s a small step in a long journey to adjust to climate change, and like the improved water systems, it’s a short term solution that doesn’t change the daunting prospect of eventual retreat to the big island.

The betel nut crisis has also gotten a short term fix, but one that hints at the kind of model islands will likely depend on more as the impacts of climate change widen. The chief has secured a regular flow of betel nut from family members who have moved to the island of Santa Cruz. Locals who make the four hour crossing have accepted that carrying in bags of betel nut is part of the adjustments to climate change.

While the chief is happy with the arrangement with family on the other island, as the stresses of drought widen and other food sources are threatened, the averted crisis only underscores the vulnerability of Fenualoa and the fragility of their survival. Today it is betel nut that is suffering and a solution has been found, but if coconut failed or faltered, the community would face a hunger crisis within weeks.

——

Walking through the forests of fruit trees and listening to the birds and sounds of children playing, it’s easy to see the reef islands as the Pacific idyll. No cars or bikes on the Fenualoa means that everything moves at a human pace. The friendly sound of neighbours greeting each other as they walk past rings through the coconut groves, and the footpaths are lined with flowers and plants with impossibly bright leaves of yellow and deep purple.

But there is a dark side to Fenualoa that becomes impossible to ignore. One day the chief invited me to come along with him to settle a case of a teenage girl who was raped by a man in the community. The chief listened to all sides and then set the kastom price to settle the argument. In this case the man had to give a few pigs and bags of taro to the family. No police, no jail time for the child sex offender, just shake hands and he goes on living down the footpath.

While the visible signs of domestic abuse are harder to spot on Fenualoa than they are in big towns like Honiara, signs of domestic strife were just below the surface. While walking back to the chiefs place, I came across a leaf hut that was on fire. A group of boys were poking at it with long sticks and the wooden frame was all that remained of what was a fine looking kitchen shelter. Amid the excitement of the boys, the wife of the chief sat to the side and wailed in grief for what was happening. A father who was furious with his disobedient children decided to burn the kitchen so they have nothing to eat and he stormed off leaving everyone stunned by this act of violence designed to send a message to his family. As the cinders smoked, the boys jumped into the smoking carcass of the kitchen and threw gang signs for the camera, showing how tough they were amid the charred remains.

The ecological equilibrium the community practices in their farming and fishing might lead one to exalt the people of Fenualoa as some saints of climate change: the innocent victims of capitalism’s relentless assault on the planet. But the community has a mixed record on marine conservation, especially when it comes to dolphins and sea turtles. A decade ago they worked with an NGO to create a marine reserve on the other side of their reef. Fishermen say the restriction has helped the overall number of fish expand. So far so good.

But each year the community organises a mass hunt for dolphins. Groups of boats go far out to sea and then drive a whole pod of dolphins into the lagoon to be killed. Locals explained that they are helping the dolphins kill themselves as Fenualoa is known in the dolphin world as the place to come and commit mass suicide. I was told that if they did not kill the dolphins, the animals would smash their own heads on the shore, bludgeoning themselves to death. Hmmm.

If that seems implausible, it at least offers some justification. Even with the cultural sensitivity, it must be a gruesome sight of hundreds of dolphins being carved up on the shore of the lagoon while the water runs red with their blood. But the treatment of turtles doesn’t have this altruistic fiction of assisted suicide.

Turtles are killed, eaten and some of their shells are sold. Officially hunting turtles is banned and the trade in shells controlled, but it’s clear that enforcement is slight this far from conservation areas and government officials. As I swam in the lagoon one evening, the severed head of a sea turtle brushed my skin and gave me a fright as I floated on my back watching the stars emerge in the twilight. Having seen a majestic leather back turtle from the cliffs earlier that day, when we exchanged glances and I stood speechless at the turtles’ beauty and grace, I could not help but feel an even greater sadness to see this reminder that turtles are considered a traditional food source and it will take decades before those values shift.

Saddening though these realities are, it’s important to place the impact of these practices in context of global ecological consequences. A few communities in the Pacific hunting dolphins and turtles is regrettable but it’s a tiny fraction of the impact hat the economic systems of extractive capitalism and disposable consumerism have on marine life worldwide. Of course it would conform to our idealised version of remote Melanesian communities if they were defenders of all aspects of nature, but the paradox of their traditional beliefs forces us to confront a more complex picture.

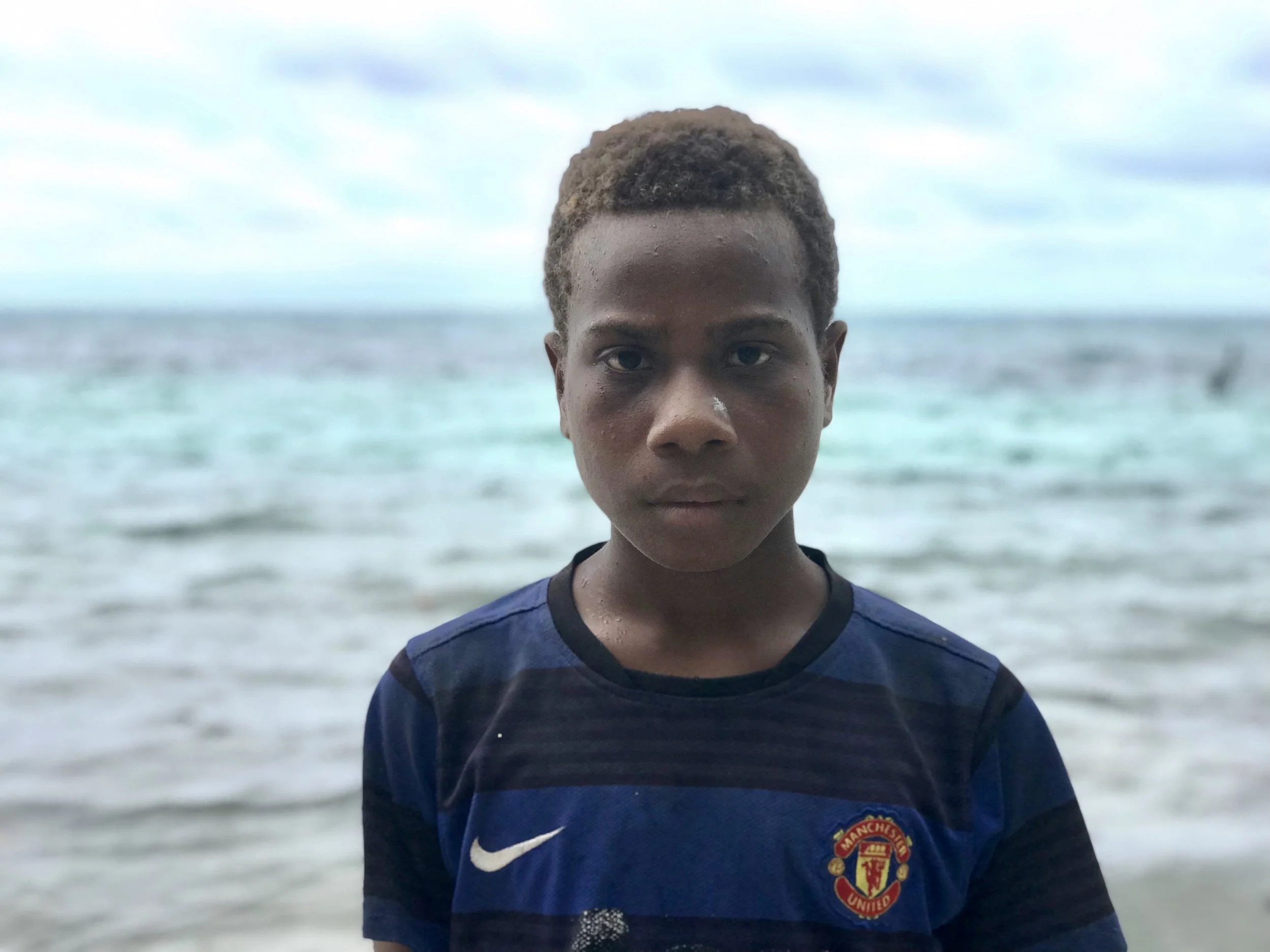

Fenualoa has a population bubble of youth, just like the rest of the Solomon Islands. More than 20% of the population is under 24 years old. For young people, the reef islands certainly have a picturesque side. School is a short walk through the forest and in the afternoons all the children gather at the the sports field to play games. The boys play soccer and the girls play volleyball and those not playing games just stand around and giggle and gossip and do what young people do all around the world.

Getting a young Melanesian boy or girl to overcome their acute aversion to individual attention and do a video profile was a big challenge. Even more intense is their shyness that comes from growing up in a village like Tuwo, where your place in the order of the community is well defined and variations from it are few. Posing for portraits was okay and even doing short slow motion clips seemed to break the ice, but the moment that the talk turned to interviewing one of them, the children literally scattered into the bush.

I thought there is no more emotional way to think about climate change that through the eyes of the children of Fenualoa but the children did not want to cooperate at first. I approached the school to see if adding a degree of authority and seriousness to the youth radio project would help overcome this timidity.

The school the only two-storey building on the island. It’s also the only building made out of non-local materials of milled timber and concrete. The principal is a kindly man from Isabel province and he’s helpful in choosing children we can work with on climate change question.

Once we got through the excruciating timidity of the girls and the diffident, too-cool-for-school attitude of the boys, the children took recording equipment out in to the community and began asking people these basic questions: When did you first learn about climate change? What do you think about the future of the island? and whats your message for the world?

I was amazed with the quality of the interviews they brought back. They recorded dozens of perspectives from people in the community and got them to open up in a way that would have been impossible for an outsider like me. People talked about their pain and frustration having to move their homes again and again to retreat from the sea, they spoke of their fears for the future and they universally expressed a heartfelt plea for the world community to help them cope with this colossal task before them.

The excellent material they brought back stood in sharp contrast to my ongoing attempts to get children to open-up on camera. I spent more than an hour filming a teenage boy doing soccer footwork tricks in the hope that he would open up on camera. It didn’t work. When I started asking him questions about his thoughts, there was a panic in his eyes and he refused to speak. I had a nearly identical experience with a young girl.

As I asked the question, I could tell that all she wanted to know from the translator, who happened to be her older sister, was “What does the white man want me to say?” Unused to being asked for her thoughts, she was unable to express them and she only wanted to get through by reciting what she was told.

In the end, instead of looking for a child, a child found me. Nathan is the 6 year old nephew of the chief. Every morning he’d stand and curiously observe me getting ready for my day. Whenever I looked up he was standing in the doorway or the window. In the end I realised that I could just work with him hear his perspective on climate. For most kids, it’s a visceral fear of the sea coming into their homes based on recent memories and maybe even watching their neighbours lose everything. Beyond the fear there’s a deep uncertainty about the future of the island that kids are picking up and Nathan expressed both of these feelings that I I heard echoed again and again in almost every home I visited.

——

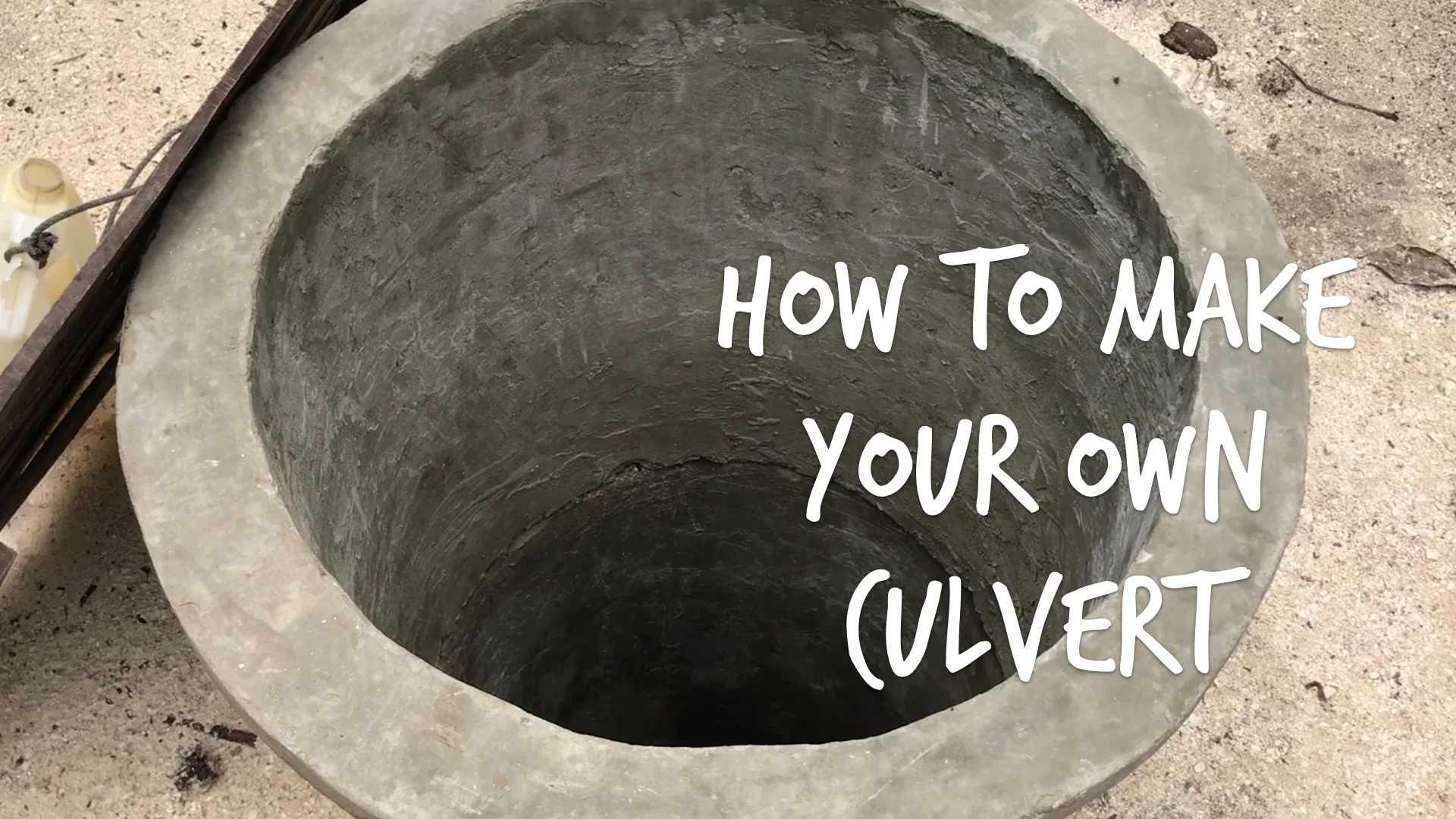

The government upgrades of the water systems can have unintended positive consequences. The past year of seeing water experts design systems and specialists building wells and installing pumps has prompted a community wide discussion about water. Joe is a builder from Malaita who married a local woman and lives on Fenualoa. He saw the concrete culverts being stacked in the wells to keep the water clean and he realised that he could make one himself. Using chicken mesh and steel wire he builds a frame and shapes a concrete culvert. He’s fixed up his well and he’s now helping his family members do the same. Joe realised that he doesn’t need to pay the transport costs from Honiara and that he also doesn’t need to wait until the next round of government support to get his well working better.

As with Janet, spending time with people like Joe inspires a confidence in the future of the community because you can see the self-driven solutions, the capacity to improvise and adapt. These initiatives are not being directed by the chief or the elders or the UN or the government, but by their own ideas. Both Joe and Janet have taken their own steps to adapt to climate change and they share a willingness to see others trying their ideas as well.

---

On my first day on Fenualoa I asked the musicians of the community to come up with a song about climate change that they could perform and I could record. I wasn’t sure what to expect and the assurances from the musicians were vague at best. By the time Saturday came along, we all gathered in the forest and the whole community stood round to watch. To my surprise they opted to perform with both men and women, and in a refreshingly honest mix of western clothes with traditional elements added, they performed a variation of kastom rain dance. Holding spears, and oars and keeping the beat with coconut shells, the group whooped and sang about the changes they see in the climate. In the Aiwa language of the reef island people, there is no word for climate, so the lyrics to the song say:

Times are changing, we can see it with our own eyes

In the context of the song, climate and time are interchangeable and occurred to me how brilliant this ambiguity is. Time and the climate are the two forces that the islanders cannot control and sadly they are now two things they are running out of.

The song presents an impassioned plea for help, or at the very least better understand these people who are suffering the effects of climate change. A century from now It’s unlikely that life will be as it today on Fenualoa. The culture will be scattered, even if the transition is managed well and smoothly, and that is a big if. In the singing and the music is something that climate change will also wash away, the cry of a culture before it is consumed by the sea.

---

As the dark undercurrents of teenage rape and dolphin slaughter suggest, Fenualoa is not always paradise. In the small strip of forest, there’s a stone fortress, like a crudely made castle where the community would hide to protect women and children from attackers. Neighbouring atolls are occupied by Polynesians and over the past thousand years, they have had a more than a few battles and massacres. The walls are crumbling now and the breadfruit trees push up the stones with their roots. The fortress is a reminder that the island has faced enemies before and endured. The survivors pull together and carry on the unbroken line of their ancestors who are buried in the soil beneath their feet. But this time, the enemy is impossible to stop and stone walls will not be enough.

The chief sat and listened to the cross section of voices recorded by the girls for the radio project. He’s heard it all before, but maybe never like this, so distilled, so succinct and so full of fear. There’s talk of buying a tract of land on the bigger island and arranging a transition of 20-30 years. But the community has no capital to buy large plots of land and the cousins and uncles in Santa Cruz won’t have enough space for everyone.

In a country that seems to be crippled by land disputes, the chief knows that his people are in a bad way. Unable to buy land, they will likely be at the mercy of host communities and the most likely scenario is a dilution of Fenualoa into small pockets in towns like Lata and cities like Honiara.

The chief says he was overwhelmed when he was entrusted with the responsibilities of being chief when he was just a young man in his thirties. Now in his fifties he wears the authority with grace and kindness, the kind of leader who listens and works toward harmony with a sense of the long view. But now the long view holds only bigger and bigger challenges that will need more than traditional ways to get through.

As the boat cuts through the still waters of morning towards the rising mountains of Santa Cruz, I recall the kastom story about how the island was pulled from the sea in a fight between two volcano brothers. The myths of the reef island people talk about cataclysmic movements of the earth and give the natural forces human stories of meaning. They have been through centuries of eruptions and earthquakes and have kept their culture flourishing. As I reflect on the resilience of the people of Fenualoa to get through these disasters and changes, I am reassured by their capacity to endure. We now face an intensification of climate change in the decades to come, and they will need to draw upon these reserves to get though once again.