‘La Riposte’

18 months into the Ebola outbreak in Nord Kivu, the vaccine is working and new cases are dropping as normal life begins to return. But the complex challenges that existed before Ebola still remain for this part of eastern Congo. Survivors are many but their journey of recovery will take time.

Cecil is an Ebola survivor who is looking after her friend ‘Sophie’ while her mother recovers at the Ebola Treatment Centre nearby. Round the clock, one on one care is provided to every child to help reduce the stress of separation from their parents while they are in isolation. Dozens of survivors like Cecil are able to look after the children because they are immune to the virus and they represent a critical intervention for children in the Ebola crisis.

Mangina is ground zero for the recent Ebola outbreak in Nord Kivu. In late 2018 the small town started to receive a flood a cases and even the medical teams at the hospital got the disease. Today it’s the centre for treatment for dozens of small communities on the roads leading into the forests all around the town.

Aloya is a small community in the center of the Ebola outbreak. Resistance to vaccination and suspicion about the disease are strong in this remote community. Skeptical leaders have been invited to see the conditions at the treatment centers so they can encourage their communities to protect themselves and get vaccinated. The message is getting through and there haven't been any news cases in the town for over 4 months, but the risks for ‘riposte’ allies remains real with leaders sometimes killed by groups hostile to the Ebola response.

Primitia Power works on one of the ambulance teams that’s specially trained to get suspected Ebola patients.She and her colleagues follow rutted tracks with their ambulance to get there quickly and contain the disease. She says it’s stressful role and they have to be vigilant about the disease, but also about the hostility of community members. They often face skepticism and even violence when they arrive and community teams come along to explain what’s happening with the protective suits and the ways to protect your family from the disease.

Health workers in protective suits decontaminate a patients ‘room’ at the Ebola Treatment Center in Katwa near Butembo. Teams of workers get the trained hygienists ready to go into the quarantine zone to and sterilize every room, every day. An empty room is not as ominous as it was a year ago when the mortality rate was much higher. Early treatment and good care mean that more than half of Ebola cases now recover.

The forest outside Beni quickly become dense and impregnable. Swollen rivers and muddy roads make it hard to deliver vaccinations or get patients in for treatment. But the forest also holds dozens of Ebola cases that go undetected. When people develop signs, doctors say that nearly a quarter some flee into the forest making it harder to track and eradicate the disease.

Kavugho and his siblings were terrified when people started dying Ebola in their town. Rumors spread that it was airborne and you might die if you go to the market, church or school. UNICEF organized local community teams to visit household like Kavugho’s and explain about the disease and how to protect yourself. His mum Nglilongo is convinced and she took the 3 children to be vaccinated so they can live without fear.

Health workers mark the name of the child on the cross before they transport the body to the burial site. When handling the body, the teams wear protective equipment for all deaths in the hospital as a precaution against Ebola. Families are allowed to watch from a distance but the traditional burials have had to be modified to help reduce transmission of the disease.

Yves runs Tele Espoir Radio in Mangina. It’s one of dozens of local broadcasting partners that help spread the word about the risks of Ebola. They program their signal to play regular spots to educate people about the disease. They also host live talk back sessions to answer questions and assuage fears. “It was critical for radios to participate in airing messages on Ebola Virus Response,” he says. “It’s only through radio that we can reach a large population.”

The face of a killer virus has been emblazoned on the vests of government health workers as a visual reminder of Ebola. The response has become ubiquitous in Nord Kivu and is welcomed in most places for containing the outbreak. But pockets of resistance remain from local leaders who see the government presence as a challenge to their authority.

Semida is a pharmacist nurse inside the Ebola Treatment Center in Mangina. She and her colleagues have been working round-the-clock to contain the deadly disease. Early treatment is critical and regular medicine during the quarantine period is key to survival. Nearly half of Ebola patients now recover thanks to the efforts of health workers like Semida.

Butembo is known a city known for its bustling markets and canny merchants. Traders come and go from all around, and last year one of them brought Ebola to the city. Dense urban housing and inadequate sanitation made Butembo the tinderbox of the outbreak. In late 2018, Ebola jumped south of Beni, to one of the biggest cities in the region.

Moise is an Ebola survivor but his story is complex. When he got sick, his parents refused to take him for treatment because they didn’t believe in the virus. As he got worse, he ran for help and was treated at the nearby center. He made a full recovery but his parents still haven’t forgiven him for his defiance. He lives on his own in a rented room and worries about his future.

Gladys works in the red zone at the Ebola treatment center in Katwa near Butembo. Everyday she gets suited up with multiple layers of protection so she can go in and disinfect the patients rooms. She says she worries about catching the disease, even with the precautions. Some of her colleagues have been infected so the dangers are ever present.

Francine is an Ebola survivor who now looks after children in the treatment center. Children suspected of having Ebola are separated from their parents so Francine is there with cuddles and care.

Health workers carry the two small caskets holding newborn twins who didn’t survive. Burials on all reported deaths, even without Ebola, are carried out by the specially trained teams, but some families don’t report deaths and still bury the family member themselves. Funerals can also be the scene of explosive grief and even violent attacks on the teams consulting with family or conducting the safe burial.

Vaisiki is 15 years old and he’s from Mangina in Nord Kivu, where outbreak that started last year. Ebola spread to Vaisiki’s home and before they could get treatment, family members died suddenly. “When Ebola came, my sister died then after two weeks my mother died as well,” he says. As an orphan, he’s been identified as vulnerable by a caseworker and he gets food to stay healthy and school and medical bills paid. For Vaisiki, life has returned to a normal routine of school and home, but so many things will take time to process. His ordeal comes in the context where the whole community has been thrown off balance by the disease and it’s only now, with support, that things are coming right.

Ange is a psychologist who works with children and adults who’ve recovered from Ebola. She helps them process what they’ve been through and cope with the grief and loss of losing loved ones. Survivors described the importance of these counselling visits to help them cope with issues like stigma and depression. Ange visits her ‘survivors’ often and develops a close relationship with them to be able to support them where it’s needed.

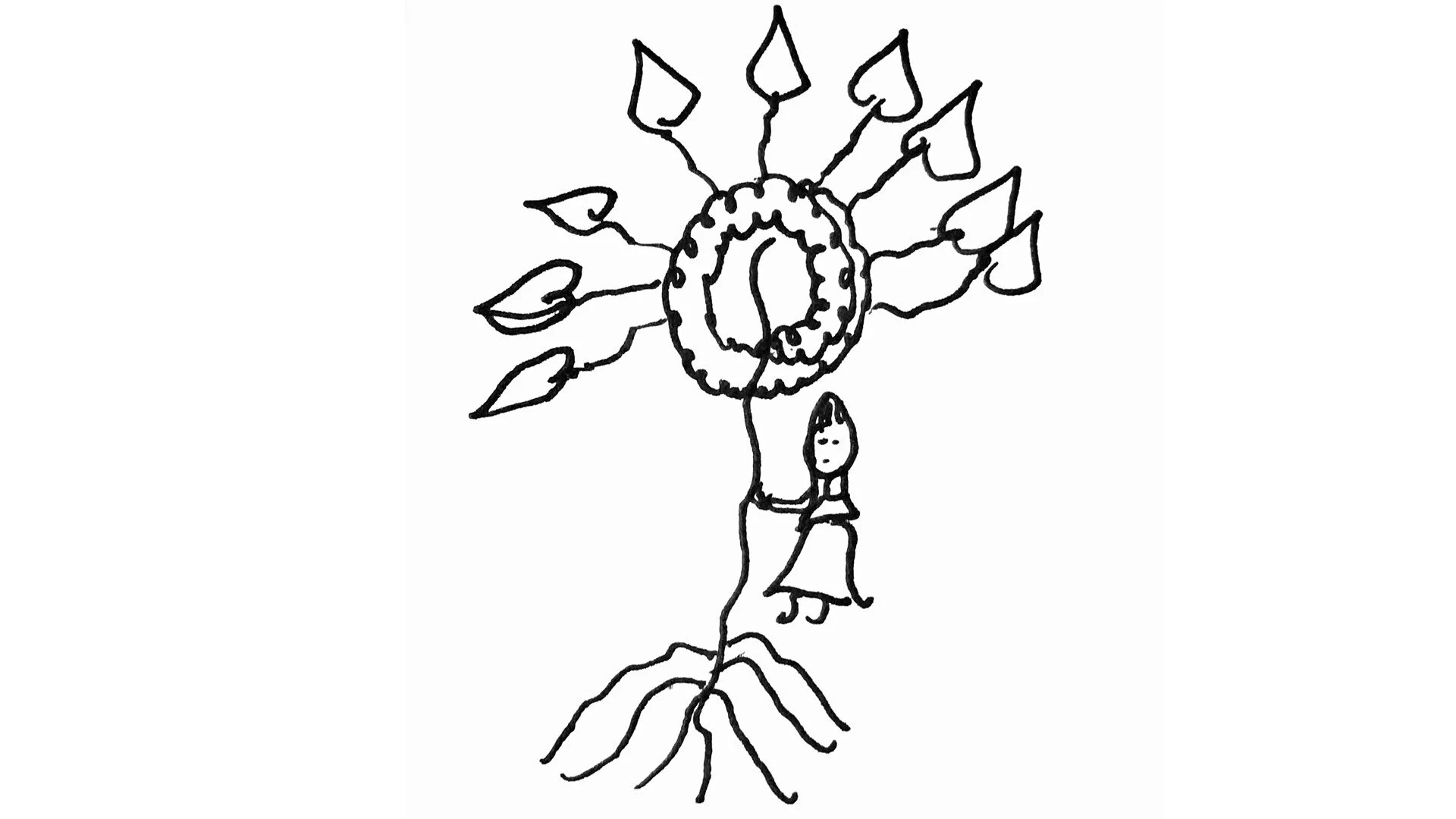

Drawing by a 14 year old Ebola survivor named Oripa in Beni. Last year she lost her mother to the disease and then got sick with her little sister Lorene. Her relationship with her little sister has deepened after what they’ve been through together. When asked to draw a picture of her family, she first drew herself standing next to her mother, and then she drew this tree, and next to it she drew her little sister touching the tree. When asked about the meaning of touching the tree, Oripa smiled. “She’s being healed,” she said. They both recovered and they’re in school with UNICEF support.

Oripia, age 14, Ebola survivor in Beni.

Drawing of a 12 year old boy who survived Ebola but suffered from stigmatization when he returned to school. “His friends were afraid of him and wouldn't play with him,” says Grâce his school principal. The school hosted special discussions to help children understand that Ebola survivors are not contagious and they can welcome their friends back into the classroom.

Mairi Is 12 years old from Beni. Her community has been hit hard by the Ebola outbreak in Nord Kivu. One of her classmates Honoré, got sick and went to quarantine for treatment. Masiri and her friends were given special classes on how to stay safe from Ebola with prudence and regular hand-washing. Now that Honoré has recovered, the class has been taught how to make him feel welcome and included.

Lorene is 8 years old. She and her sister survived Ebola together in quarantine. They lost their mother but they’re recovering and back in school. This is Lorene drawing a self portrait with a chicken.

This is Lorene’s drawing.